|

| |

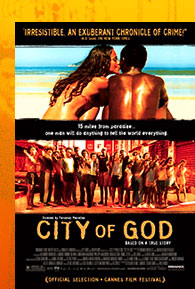

City of God, the film: a bag of crimes by Katia Santos

One day in December of 1988, I stayed up talking with my mother until 2 am

and at 6 am without any signal or notice she was dead. Destiny. At that moment I

decided that nothing in life was important because life would always play a

trick on you at the end. The first target of my revolt was exactly my mother.

The first thing I did when we got back from her burial was to move

things around in the house, do everything opposite from what she liked: I

threw out the horrible kitchen cabinet, took down the tacky living room chest

and gave out the horrendous porcelain decorations to my neighbors. I

transformed my pain into anger trying to continue existing, but it didn't really

work. The house just ended up feeling emptier without her or the things that

marked her "style." One of the last things I got rid of was a blue plastic

bag that she guarded with all the care of a collector, full of newspaper

clippings of crimes committed in our neighborhood, our "community": City of God.

When I found the blue bag, I sat down for a while and went through

the clippings. I recognized the people. I wasn't able to stand the sad

sequence and didn't even make it half way through the clippings. I put them

back in the bag and went straight to the trashcan. I had never liked that

sick collection. I was finally getting rid of it.

All of this to say, that that was the same sensation I had when I

watched the film City of God. It was like they had opened the blue plastic

bag and given life to the pieces of texts and the images. The only difference

was that now I didn't have any power over the blue bag, I couldn't stop

the twisted and macabre sequence. It didn't help either that the sequence was now

being presented to me in the North American mold of cinematography with its

beautiful images and special effects. Like all "great" North American

films, I would have been okay missing this one. But, I was at the movie

theatre with a friend that was "entering" into the City of God for the first

time through that huge authoritative movie screen. I couldn't leave her in

the middle of all those shoot-outs.

Since I wasn't in Brasil when the film was released (I've been in

"intellectual exile" in another country for two years), I read a lot

about the film, talked about it through email, and everyone always had good

things to say. Up until then, however, I hadn't heard the opinion of people

from City of God. When I found out that they were going to screen the film in City of God, I

wrote my brother and asked his opinion and how people had reacted. He is one

of those people who is very economic in his writing and this time wasn't any

different: "I didn't see it and I'm not going to. They screened it.

The people that saw it hated it." What do you mean hated it? That

information did not match up to everything I had read. I was intrigued. But in

reality, it wasn't too hard to imagine why there was that difference of

opinions. Some residents of City of God were somewhat satisfied with the

existence of the film because it gave them some visibility. Now they could give

all the details of those crimes to the lay people. A few people who lived

there during the time period liked it and even found it funny. I still

hadn't consulted a person that for me serves as a sort of thermometer for

the City of God: the rapper MV Bill. He didn't go beyond what I had read in

some papers, " Listen, the film is aesthetically well-done, everyone is

saying how the photography is this and the other, but it is a film totally

without love, without hope, with no signals of life aside from crime." I was

even more intrigued.

I was in Brasil in December and spoke with many people about the

film, but wasn't able to watch it. In January, a whole controversy started when

MV Bill decided to publicly state that the only result of the film had

been to carve into stone the stereotypes contained within it. He was

demanding that this place of so much misery also receive some sort of social benefit

after the ultra-negative exposure that its residents – the ones who have no

involvement with the drug trade, or in other words, the overwhelming

majority- were subjected to as a result of the film. I started

thinking about all the wonderful things I heard from friends who don't live in City of God

or any other similar place. My question was: what had led MV Bill to assume

such a contrary position from the general opinion? He was clear, "You can't

understand because you haven't seen it. Watch it and then we'll talk.

You live here, you will know what I am talking about." I didn't have a

choice. In the beginning of February, I watched the film and instantaneously

returned to my mother's blue plastic bag.

But City of God is not my mother's blue plastic bag of crimes; it is

not only a mound of crimes and criminals.

I know that the argument could be made that there wasn't room for

anything else in a film that was already so long. So what? Does that mean that

we cannot express our anger? If the film were a documentary about Zé

Pequeno-, which would have been more appropriate because of the emphasis on him-

, the anger would still be there. He didn't have parents? He didn't have

family? He did, of course he did, and they were well known. Even though he

was the center of most of the narrative, there wasn't room for those details.

There might have not even been enough time to check his life story because

Pequeno, if I'm not wrong, died during an attempted "invasion" of an

apartment after having lost the local drug "post."

And since we're talking about invasions and family, I do recall that

in the middle of a shootout where he challenged the local power, realizing

that they were not coming after him, he leaned against a wall and shouted

to someone, "go get my grandmother, kid." His request was granted

quickly and his grandmother showed up. She was (or I don't know if she is still

alive) a small, black woman who was very quiet. At that moment he looked to

all sides, put down the guns he had in both hands, and said "Your

blessing grandma. Don't worry. Everything is fine." Then he hugged her, never

letting go of the guns.

That probably only lasted three minutes. We couldn't hear what his

grandmother was saying from our windows. But I never forgot that

scene. It was very bold. In the middle of a shootout, both of them could have

died right there, him and his grandmother, during their hug. But he wanted

to see his grandmother and she responded to her grandchild's plea, who

happened to be Zé Pequeno, but he was also her grandchild. Even though some may not like to accept it,

people who are involved with crime, do have families that love them.

That is one of the gravest sins of the film City if God – the

dehumanization of everyone and everything, disguised as fiction based on reality.

Things are not quite like that, we know better. Someone birthed Dadinho.

Someone cried for Zé Pequeno, the criminal. But the impression the film gives

you is that Black people sprout from the ground, they just appear from nowhere with

guns in their hands. Everything was exactly like my mother's blue bag of

crimes. In that blue bag, there also wasn't anything about the criminals or the

victims' backgrounds. Aside from the son of the fish vendor, no one

had a family inFernando Meirelles' City of God. There was just a bunch of

Black people dying or killing. I guess all that extra information doesn't

sell newspapers or movie tickets.

And since we are talking about Black people, I was also intrigued by

the casting choices. Bené, who was the good guy, was light skinned. Zé

Pequeno, who is undoubtedly the "bad guy" was as dark as night. It's

interesting because in real life they were both very light skinned. They

physically looked alike. And what was the criteria for the choice in casting?

Coincidence? Chance? Sure, Sure.

While, Bené was still alive on the big screen, we had some refreshing

moments. I even thought I would see the little park where we used to

play. On summer nights, some mothers, including my own, would come down to

the park. They would all talk but in reality they were there watching us.

The park was beautiful filled with people. Everyone very tanned –

everyone, black people, white people and all the nuances that exist between

those two colors. And everyone was always attentive to any movements that might

lead to a shootout. The drug dealers would be on one side of the park and

we on the other. Back then, the dealers didn't exhibit their guns. We would

just know because of the bulk under their shirts. What was really sad, though, was when the mothers

started singing that old song "it's time to go, let's go, I have to go to

work tomorrow and you are going to wake up late for school." Those that

remained in the park after the collection were there because they were

starting to "get involved" in some way.

I thought we were going to be able to have a truce during Bené's

going away party. I thought finally, they are going to show how the residents'

led their life. Believe me, this would have contributed a lot to a film

that intended to be a picture of a community since the name of the film

wasn't The Saga of Zé Pequeno, but rather City of God. Unfortunately, that side did not

interest the directors. They knew that their "target audience" would not be as

interested if the film showed that people who live in favelas or shantytowns

have pretty regular everyday lives. I know, it just wouldn't have

been as interesting. But I don't accept that!

And don't come tell me that you cannot argue with fiction. When a

director puts guns in the hands of children under the age of 10 and gives out

the addresses of those children, fiction is invading reality. In which

case, fiction can be invaded by reality too. In real life, none of the kids

that took over after Zé Pequeno were under the age of 15. But what has more shock value, a

six year old with a gun or a 15 year old? One of the most shocking scenes of

the film is when one child is pressured to shoot another. I am not saying –

unfortunately- that that scene may not be happening right now. But if

we are talking about the era of Zé Pequeno, the scene is not accurate.

The people who are "in love" with this film, just like those who were

involved with it need to understand that we are talking about a

population that exists, is very much alive, and that is entitled to have

reactions. According to general opinion, it is not surprising when some

favelados (those who live in shantytowns) close down a street and burn some buses, after all they

are favelados. It is shocking, however, that those people would dare to

criticize a cultural product of the category of this "our" national

and international success. Well, I am very sorry! The times, when that

said favelado was spoken about as if "it" were from other planet, are long gone. We are right

here, real close, watching and hearing everything. And if we don't like

something, we will say it. That's democracy. And it needs to be broad and

unrestricted! It is there for Paulo Lins, for Fernando Meireilles, for MV Bill and

for Dadinho's mother as well as for the family of Zé Pequeno. Just like it needs to

exist for any resident of City of God that feels marginalized by the film

and wishes to put their mouth on the bullhorn.

Written by Katia Santos

Translated by Loira Limbal

Related Links:

Miramax | City of God Official Website

Official City of God Website - Brazil

|

|

|

|